In this new series, we follow Ian Furby as he sets off circumnavigating Great Britain in an 18ft speedboat

I am fifty-three and a half years old, a proud Yorkshireman and a self-confessed boat addict. Thankfully, I have a very understanding family who share (or at least put up with) my passion.

I’ve been involved with boats for more than 30 years. In my 20s, I was an avid wreck diver and for several years I was both crew and a helm on the Runswick Bay Rescue Boat.

I have my yacht coastal skipper’s certificate and various other powerboat licences. I own a Nordkapp Enduro 550 called Summer Buoys that I bought in 2015 for £25,000. It is 18ft long and powered by a 115hp Evinrude ETEC outboard engine.

Adventure beckons

These days, my family and I do most of our boating out of Runswick Bay, North Yorkshire, where we’re fortunate enough to own a cottage. If you’ve never been, don’t come, it’s horrible! Just kidding; it’s a beautiful Cornish-type coastal village with narrow winding lanes and an incredible sandy bay that won the best Best Beach in Britain award in 2020. The Royal Hotel pub overlooks the bay with stunning views of the Jurassic coastline. Runswick even has its own microclimate, hence its nickname, Runsbados.

We’ve enjoyed many years boating with the kids; fishing, water skiing, wakeboarding and doughnut-towing but my favourite thing is to “go on a trip”. When I first started boating from Runswick, a big trip would be 6nm south to Whitby, from where Captain Cook set off aboard the Endeavour to find the world.

But one day, a few years back, I encouraged three other boats to join me on a massive voyage to Robin Hood’s Bay, some 14nm south of Runswick, doubling anything we’d ever attempted before. Some in our flotilla were concerned about which time zone we were steaming into and whether we’d need to take euros. We survived unscathed and now do it regularly.

Launching at dawn on Day One following a 3am wake-up call. Photo: Ian Furby

We go in an hour before low water, beach the boats, lob out an anchor front and back. The tide goes out for an hour, then comes in; giving us just enough time for fish and chips and a couple of beers. It’s ace.

After our brave escapades to Robin Hood’s Bay, we got adventurous. Two of us set off to Filey, 30nm south, and once we even went to Flamborough Head, 35nm south.

Hatching a plan

Then Covid hit. The longer we were locked up, the more I dreamed about a rather bigger adventure for me and my boat – not just a round trip to another bay but a trip round Britain.

All of it. This is a journey of 1500-2000nm, depending on how closely you hug the coastline. So if I did 200nm a day, it would take ten days to get round. Simples!

Slowly, I hatched a plan to test the boat and myself. I plotted a course to the Farne Islands, 75nm north-west, and waited for a weather window. I found someone daft enough to join me (cheers, Shehan) and at 6am one July morning, we set off.

A mixture of excitement and trepidation prevails as Harty (right) and Ian (left) set off. Photo: Ian Furby

Summer Buoys can pull over 40 knots on a flat day but its comfortable cruising speed is 22-25 knots. We straight-lined it there but a southwesterly picked up on the return leg and we had to hug the coast and stop for fuel in Amble. We got home 12 hours after our departure, having clocked almost 200nm.

The trip taught me a lot. The return leg was pretty bumpy and I had to stand to absorb the worst of it but after a few hours the pain in my knees and hips was horrendous. I couldn’t afford to fit suspension seats so I sourced a 30mm-thick rubber crash mat (the sort they use in a gym), cut it to size and fitted it to the cockpit floor. In conjunction with an old pair of Adidas Ultraboost running shoes I’d taken to wearing on board, I was confident I’d sussed it.

When news spread that we’d been to the Farnes, everyone thought I’d lost the plot. Best not tell them my actual plan, then!

Planning permission

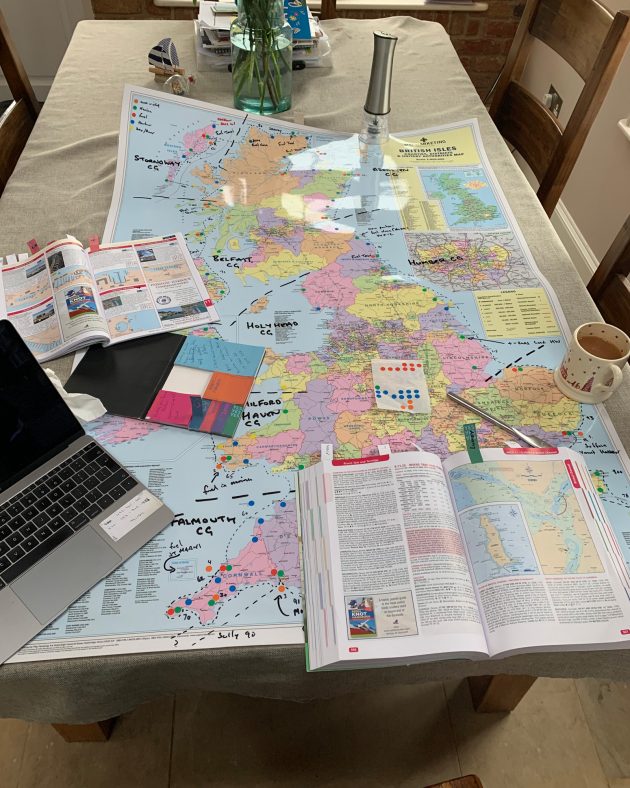

I bought a big map and marked every marina, harbour, bay and river that was a possible safe haven with coloured sticky dots. Then, using the 2021 Almanac and UK Marina Guide, I plotted my voyage. Summer Buoys has a 100-litre inboard fuel tank and I could carry a further 100 litres of fuel in plastic jerrycans, giving me an effective range of about 200nm.

Runswick Bay’s Royal Hotel pub. Photo: Ian Furby

My plan was to set off at 4am every morning to take advantage of the calmer water, travel for four hours or so, then either continue if conditions were suitable or relax during the day and set off again late afternoon.

I worked out each day’s intended destination and marked them on the map. I also plotted minus ports if things weren’t going so well and plus ports for when they were, with safe havens in between. I chose most of the ports based on the availability of fuel. Not all marinas sell petrol, and Summer Buoys likes petrol. Lots of it. I searched Google Maps for petrol stations close to marinas and avoided any that were more than a ten-minute walk away. I plotted them on the map too, along with screenshots of the route and all the information in the Notes app on my phone.

Next, I marked weather stations, webcams and all the relevant coastguard areas using colour coded dots: green for marinas, blue for harbours, yellow for rivers and bays, orange for overnight stops, red for fuel stations and squares for weather stations and webcams. The map was now starting to look like a teenager with acne.

Photo: Ian Furby

In between plotting routes, I was constantly thinking about equipment, spares, and kit that I might need. Every time I thought of something, I’d make a note on my phone and check it off when I’d sorted it.

Amazon was delivering daily and there was an enormous pile of kit stacking up in the corner of the dining room; spare prop, battery, battery charger, fuel filters, tools, cable ties, gorilla tape – you name it, I had it. Using some aluminium checker plate, I even adapted a folding sack barrow to carry all four of my 25-litre jerrycans.

Most of the planning took place during lockdown and was a welcome distraction for me. I’m not sure my wife, Sheddy, thought I would go through with it and, if I’m honest, I wasn’t sure I would either but I thought I should at least check she was OK with it on the off chance that I did.

I plucked up the courage to ask her, staying out of striking range, just in case. “Sheddy, I’m serious about this. Are you OK with me going?” “How long will it take?” she asked. “Ten or eleven days, if it all goes well,” I said, still keeping my head down. “What are the chances of it all going well?” “Slim” I replied. “Who’s going with you?” “Nobody, at the moment. I’ll do it on me tod if need be.” She went off and looked at my life insurance policies, then agreed.

Article continues below…

Safety first

It was now early June, and I was ready. Various routes had been plotted to allow for sea conditions and wind directions. I had the latitudes and longitudes for my destinations, harbourmasters’ telephone numbers, VHF channel numbers, port access times, locations of fuel and bail-out ports.

This had all been printed out, laminated, and made into a flip folder. I cut down the big map with all my coloured dots and made it into a flip chart, along with the almanac and marina guide. I’d thought through the plan as much as I could but sometimes you just have to take the plunge and figure out the rest as you go.

I had a Garmin plotter and Navionics software on my phone as a back-up, as well as a compass. Summer Buoys is fitted with a 25-watt VHF radio, I also had a secondary handheld VHF and a personal EPIRB fitted to my lifejacket in case I had to abandon ship. Thankfully, Nordkapp claims that its boats are unsinkable but didn’t someone say that about Titanic? I decided to take an inflatable paddleboard as a life raft just in case.

Photo: Ian Furby

Even with all my planning, I would need some serious luck along the way. I was certain that either the boat or I would break. During the first week of June 2021, the winds swung to southerlies and the sea flattened. With news of extended high pressure over the UK for the middle of June, the stars were aligning. Along the way I’d asked a few of my trusted mates if anyone would care to join me on a leg or two.

The invitation was met with stony silence but then a boaty mate said he’d come along for the first three days. This was fantastic news; Harty has been boating since Adam was a lad and had also been a helm on the Runswick Bay rescue boat back in the day. I would have gone on my own but I felt much more comfortable with an experienced crew beside me.

I figured that by the time Harty jumped ship, I should be match-fit to tackle the rest of the journey alone.

Photo: Ian Furby

The plan was to leave Runswick Bay and head south. The prevailing winds are southwesterlies, so we would be in the lee of the land until I turned into the Channel, at which point it would be on our nose, but once round Land’s End and heading north, the wind would be behind me. I also planned to cross the Irish Sea from south-west Wales and steam up the east coast of Ireland in the lee of the southwesterlies and the big Atlantic rollers.

The kids started to give me long, lingering hugs. Even Sheddy went quiet. I had a wobble. During all the intense planning, I hadn’t once thought that there was a chance I might not come back. Should I do this to my family? I figured that we all risk our lives every day when we step out of the front door, and no one worries about that. Going round the UK would be just like going to Whitby and back – 120 times. Wobble over.

D-Day arrives

Harty and I arranged to meet at Runswick the evening before departure day, intending to launch at 4.30am the next morning.

I arrived first, did some last minute prepping then headed to the pub. It was a bluebird evening; the sky was cloudless, the sea was like glass and it was due to stay like that for several days.

Three of my mates were already at the bar. They were all a few shandies in and one of them, Dobbo, seemed genuinely envious of my impending adventure. “Join me if you like,” I said. “I’m short of crew.”

“What? Er – hell, yes.” And that was that: he was in.

I wasn’t sure if he was up for it or it was just the shandy talking but I made a plan to pick him up in Oban in a week’s time. So Harty would be with me for the first three days, I’d have four days on me tod and Dobbo would join me for the last four days. Sorted!

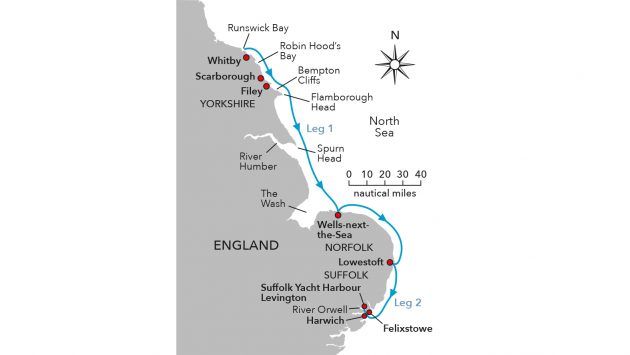

Day 1, Leg 1: Runswick Bay to Lowestoft, 160nm

I’d intended to be tucked up in my pit by 10pm but that didn’t quite happen. It was a very pleasant evening in the pub so I was late to bed and by 3am I was wide awake and bouncing off the walls with nervous energy.

I wasn’t due to meet Harty until 4.30am but I couldn’t wait. I headed to the boat, took off the covers and loaded the kit. By 4.15am Summer Buoys was locked and loaded. Harty arrived, started the tractor and we launched. Selfies taken with stupid grins and high fives, throttle down, we left the bay at 5am. It was a glorious morning. The sun was rising as we steamed towards Kettleness Point. 1nm done, 1,999nm to go.

Bidding farewell to yorkshire

Wells-next-the-Sea was our first destination. There are many stunning coastlines around the UK, and one of them happens to be in my own backyard, Yorkshire – God’s Own County. Heading south from Runswick, we passed Whitby, Robin Hood’s Bay, Scarborough, Filey, Flamborough and Bempton Cliffs.

Bempton is a conservation reserve with amazing white cliffs that form the edge of the Yorkshire Wolds. It has a vast array of seabirds, including puffins, guillemots, razorbills, fulmars, kittiwakes and gannets, so after 35nm, we stopped to take it all in. The noise of the seabirds was deafening. It was at this point that I accepted that my sonar was telling me porkies.

It said we were in 200ft of water but I could see the bottom – 10ft beneath us! “This could be interesting,” I said. “It’s a long way to go without a sounder.”

We pushed on. The sun was still with us as we passed Flamborough, from where the route would follow a straight line for 80nm. Sadly, the millpond conditions didn’t last for long. The sea lifted and our speed dropped from 25 knots to the wrong side of 20 knots.

The pair were blessed with calm seas and wall-to-wall sunshine for the first few days. Photo: Ian Furby

The further we pushed south, the less dramatic the coastline became. Spurn Point, the Humber, the Wash and North Norfolk look particularly flat from the sea but with hundreds of wind turbines to dodge, it felt like we were driving through a gigantic pinball machine, with us as the ball!

After about 50nm we stopped to refuel. The tank is good for 100nm but I like to run between full and half full to reduce the risk of sucking up any dirt from the bottom of the tank. We refuelled with the engine running using a jig syphon hose – ideally, I only wanted to stop the engine once we were safely tied up in port.

From this point on, refuelling became a pleasant routine. We steamed for two to three hours, then stopped for a much needed break. We used the time to have a pee, get more food and water from the ‘galley’ (tub under the seat) and swap drivers. Steam, stop, refuel, repeat.

The approach to Wells was pretty uneventful, with only the odd big ship to steer clear of. Then came the first cock-up.

My mind had been so set on Wells being our first port, I hadn’t checked whether it had 24-hour access. To get to the quay, you need to go up through the East Fleet Estuary. It’s tidal, very tidal. We arrived at Wells five hours after departing but two hours before low water. There were huge sandbanks everywhere. As we headed upriver towards the quay, we came across a dredger hard aground.

All smiles from Harty on Day One of their epic trip. Photo: Ian Furby

As we pulled alongside, I asked the skipper, “Will we make the quay?” He looked at his watch. “You might, but you best lean on it.” As we got closer, the retreating tide was doing about Mach 2. “Harty,” I said, “if we get in we could be stuck for four hours, minimum.” “I was just thinking that,” he replied.

We turned round and legged it back out to sea. I was annoyed with myself for wasting valuable time and making a schoolboy error; I needed to do better.

Even without looking at my passage plan, I knew we needed to push on to Lowestoft, a further 50nm that would leave me with a fuel reserve of just 40nm. We went for it. The sun was out again. Hugging the coast in the lee of the land, it was flat, and we were cruising at close to 30 knots. Happy days.

“Pot marker ahead,” Harty shouted. “Cheers, got it, bud,” I replied. I gave it 50ft. As we passed it on my port side, I glanced to see if there was any floating rope attached. There was. Throttle off and lifting the engine in the same motion, I snagged it briefly but lost it just as quickly. No harm done.

Tied up at Suffolk Yacht Harbour. Photo: Ian Furby

Exhaustion sets in

The rest of the journey to Lowestoft was pretty straightforward, other than me getting twitchy when the fuel gauge got below a quarter. We tied up to a pontoon at the Lowestoft Cruising Club, which had the best access to fuel. The club secretary, Doris, agreed that we were good to stay for an hour or so to refuel, so we loaded up the jerrycans on the improvised sack barrow and headed into town.

Grub first. We found a chippy, placed our order and collapsed on the plastic chairs outside. I was knackered. I didn’t mention it to Harty but I was starting to question whether I could keep this up for another ten days. The fish and chips worked its magic and after half an hour’s rest, my energy levels were back up and running.

Once recovered, we fired down to the petrol station, filled up, and headed back to the boat where we filled the tank, then returned and refilled the cans. Fully loaded for another 200nm, it was time to crack on.

The old pirate-radio lightship in Harwich. Photo: Ian Furby

Leg 2: Lowestoft to Levington, 45nm

Our next stop for today was Suffolk Yacht Harbour, only 45nm away in Levington. The tide had turned in the couple of hours we’d been laid up and with a ten-knot southerly blowing against the rising tide, it was a little lumpy as we made our way down the Oulton and out to sea but then the wind veered southwesterly and the water flattened.

The sun was out and we made good progress. Before long we were turning into the estuary where the River Stour meets the Orwell with Felixstowe to our starboard and Harwich to our port.

As we headed upriver, the water turned to glass. I edged the throttle forwards, lowered my shades and soaked it all in. Listening to the gentle whoosh of the bow cutting through the water, I looked back over my shoulder to watch the wake streaming out behind like vapour trails from an aircraft.

It was bliss, just bliss.

Refuelling in Lowestoft. Photo: Ian Furby

Gliding through the entrance to Suffolk Yacht Harbour, I tried to hail the harbourmaster on Channel 80. No joy, but we found a convenient berth and asked a couple of lads sitting on a small yacht where to find grub and a bed. They suggested heading back downriver to the Ha’penny Pier in Harwich. “You can tie up there for the night for a tenner and there’s a hotel.”

Ten minutes later, we were sitting on the terrace of the Pier Hotel enjoying a couple of beers overlooking an old pirate-radio lightship; the sun was setting and we were in sight of our ride. We had just experienced one of our best-ever boating days. Harty and I clinked glasses. That morning, we had been in North Yorkshire and now we were in Essex.

We’d travelled more than 220nm. Any worries I had about completing the trip were long gone.